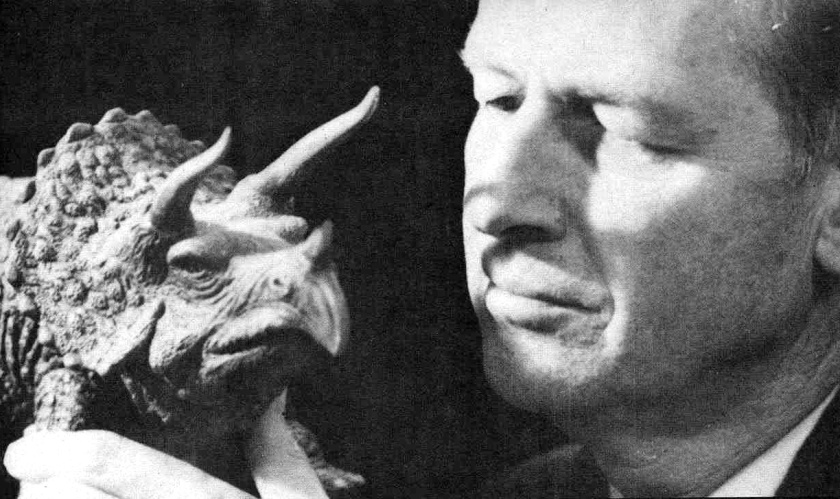

Special effects artist Ray Harryhausen watched King Kong (1933) for the first time at the age of 13. The bewitching movements of the giant ape and the prehistoric creatures animated by Willis “Obie” O’Brien caused such an impression on young Harryhausen that he was compelled to experiment and breathe life into one of his own passions: dinosaurs. After building his own articulated creatures with the help of his parents, he put together a clip of an apatosaurus fighting an allosaurus -a showreel that would eventually open the doors of the big studios for him. Throughout his career, Harryhausen revisited dinosaurs on many occasions, as well as giving life to giant apes, underwater monsters and aliens in flying saucers. But it was with his work on Jason and the Argonauts, Clash of the Titans and the Sinbad cycle that he fundamentally shaped the perception of mythical creatures in modern popular culture.

Harryhausen’s first mythological feature film was The seventh voyage of Sinbad (1958), inspired by the tales about the sailor traditionally told by Scheherazade in the Thousand and One Nights. Arguably the most popular character in the film was the Cyclops, a heavy-footed, stone-throwing giant.

The one-eyed giant appears in the tale The Second Voyage of Sinbad, “a black monster as tall as a palm tree”, with an eye in the middle of his forehead, long sharp teeth, the ears of an elephant and an underlip that “hung down upon his breast”. In the story, the cyclops examines Sinbad and his fellow sailors in turn, lifting them up and throwing them on the ground with disdain, judging them to offer too measly a portion. He finally kills and roasts the captain, the fattest of them all, and devours him.

Harryhausen’s cyclops doesn’t fit the traditional description of the monster. His is not a black giant, but a greenish, one-horned, cloven-hoofed beast, almost reminiscent of the Greek god Pan, with a furiously brutish yet expressively human face. The artist said he tried to instill him with a sense of sympathy -and this comes across particularly strongly when the monster is blinded.

But despite the Cyclops being the most remembered creature of the whole film, Harryhausen’s favourite was the serpent woman conjured up by magician Sokurah (inspired by Jaffar, the character played by Conrad Veidt in The Thief of Bagdad, 1940) in front of the Sultan’s court. With her writhing limbs and serpentine tail, her undulating, strangely sensual dance nearly ends up in self-suffocation. She is saved by Sokurah, who returns her to her human form.

Although there are no snake women in the Sinbad tales, the inspiration for the character was probably the djinn, the supernatural shape-shifting creatures of Arabian lore who often show a preference for adopting the shape of a snake. There is, however, a long tradition of mythical serpent women, from the Egyptian Wadjet to the Greek Echidna and the Hindu nāgin. With her ophidian appearance and blue-green complexion, this creature seems a clear, though admittedly kinder-looking, antecedent to the terrifying Medusa from Clash of the Titans: their creator, always working with tight budgets, would later transform the snake woman into the Gorgon.

Jason and the Argonauts (1963) was Harryhausen’s first incursion into Greek mythology, and was initially conceived by him as a mythological mash-up to be called Sinbad in the Age of Muses, with Sinbad joining Jason and his heroes to seek the Golden Fleece. The film is inspired by Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica, and contains many of the most memorable creatures Harryhausen ever created. The first of these is the metal giant Talos. In the Argonautica, Talos is a bronze colossus that protects the coast of Crete by throwing rocks at pirates and invaders. In the film, the muscular, towering statue, awakens after foolish Hercules decides to steal part of the treasure it guards. The titan lurches towards the Argos with a spine-chilling metallic creak that accompanies Bernard Herrmann’s suitably martial score. It is Jason who finally defeats Talos by removing a peg from his heel, which, like that of Achilles, is Talos’s most vulnerable spot. The Argonautica describes how “beneath the sinew by his ankle was a blood-red vein”; Apollodorus, in his Library, describes how Hephaestus had constructed Talos with “a single vein extending from his neck to his ankle, and a bronze nail was rammed home at the end of the vein”. But, whereas in the Argonautica Talos grazes his ankle on a jagged rock, in the Library it’s Medea the sorceress who draws out the nail from the titan’s heel, exactly the role done by Jason in the film adaptation.

The Argonauts encounter the harpies later in the film. In Greek mythology, harpies were winged spirits, sent by Zeus to torment king Phineas of Thrace as a punishment for revealing the secrets of the gods. In his Theogony, Hesiod describes the harpies as winged maidens with “lovely hair”, whose flight is faster than that of the winds and birds. Despite this poetic description, Harryhausen’s harpies seem to be heir to another tradition that probably started with Aeschylus’ Eumenides and that presents them as demonic creatures, closer to the furies, the chthonic deities of vengeance. In the film, the harpies’ wings are dark and cartilaginous like those of a pterodactyl, and they have dark, petrol-blue skin and short, coarse hair.

Hydra, the offspring of Echidna, the mother of all monsters, and giant Typhon, lived in the fetid swamps of Lerna and was killed by Hercules as one of his twelve labours. The Greek hero defeated it with the help of his nephew Iolaus, who cauterised the wounds to prevent the regrowth of its multiple heads until there was only one left, which Hercules crushed and buried under a boulder. Hydra had the body of a serpent and, usually, nine heads, though in different interpretations they could reach up to a hundred. Harryhausen’s creature has seven, a number that was clearly his lucky charm (The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad was also named after his suggestion of using the mystical number), and is killed by Jason.

But the highlight of the film is the battle with the skeleton army. Harryhausen had had the idea of animating skeletons for a long time: there’s already a skeletal warrior brought to life by Sokurah in the first Sinbad. The episode of the Spartoi, the earth-born warriors who confront Jason in Colchis, seemed perfect for Harryhausen’s vision. According to Apollodorus, the Spartoi were formed from the teeth of a Drakon, sowed by Jason after king Aeetes’ command. These otherwordly armed warriors were the ghosts of the ancestors of the Thebans, also summoned by the blind prophet Tiresias. Harryhausen knew that he couldn’t depict the Spartoi as rotting corpses if he was aiming for a certificate suitable for younger viewers, so he decided to use skeletons instead. The scene is possibly the most memorable one he ever shot, and took over four and a half months of work. Despite what classic tradition tells us, Harryhausen’s skeletons weren’t crushed by large stones. Instead, he had Jason jump off the cliff into the sea, where the army of the undead couldn’t survive.

After Jason and the Argonauts, Harryhausen worked again on two further Sinbad adaptations, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1974) and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977). In these he included mythical creatures such as the centaur and the griffin and gave life to the Minotaur-inspired Minoton. But the most unforgettable is Kali, the six-sword-wielding, head-sliding Hindu goddess of destruction. Her traditional garland, made with the heads of dead children, is replaced here by a belt ornamented with skulls. She is destroyed when she is pushed from a ledge and shattered to pieces.

Harryhausen returned to Greek mythology in Clash of the Titans (1981), based on the myth of Perseus and Andromeda, but with a modified storyline that allowed for the inclusion of more creatures. The final battle presents Perseus riding Pegasus, the winged horse that sprang from the neck of Medusa after she was beheaded by the hero. Perseus’s aim is to save Andromeda from being sacrificed to a sea monster. In Apollodorus’s Library, the monster was Cetus, sent by Poseidon to punish Queen Kassiopeia’s hubris, after she boasted that her daughter Andromeda was more beautiful than the Nereids. In the film, Ketos is transformed into the Kraken, a colossal four-armed humanoid creature covered in scales. Krakens, the sea monsters of Icelandic or Norwegian origin, are generally depicted as cephalopods in popular culture, probably after the description, based on oral tradition, of Carl Linnaeus in his 1735 Systema Naturae.

Although the battle with the kraken is the climax of the film, the best-remembered creature is undoubtedly Medusa. Her fearsome, luminescent green stare turns men into stone, but Perseus is able to defeat her by studying her movements through the reflection in his shield. Slithering by the crackling fireplace of a dimly lit temple, the approach of the Gorgon is mesmerising. Her uncanny movements and perverse appearance are enhanced by the effect of flickering light, proof of the artist’s virtuosity.

Clash of the Titans was remade in 2010, a decision that surprised Harryhausen, who declared: “I thought we’d made the definitive version”. The CGI, which the genius considered a tool, rather than a method of entertainment, didn’t achieve the spine-chilling effect of the most terrifying moment of the 1981 version -the killing of Medusa. Harryhausen knew precisely why: “There’s something that happens in stop-motion that gives a different effect, like a dream world, and that’s what fantasy is about”.

First published in Fortean Times no. 303

You must be logged in to post a comment.